Rabbi Mishael

Zion | Moonshine Kislev 2014 | Text and the City

|

| Odysseus Returns Home, 8th C BCE |

As the weather turns colder, the gaze turns inward. This

year’s month of Kislev is bookended by the

two holidays of the hearth and home:

Thanksgiving and Hannukah. As myriads travel “home” this week for Thanksgiving,

I wonder what makes a home worthy of its name.

I’ve been pondering this question as I’ve found myself moving

back with my own family to the same neighborhood in which I grew up. As I walk

down the familiar streets of Talpiyot in Southern Jerusalem, I keep wondering:

after all these years, does it still feel like home? And more importantly – why

do I care? As Viennese philosopher Jean

Amery asked it: “How much home does a person need?” Why does this question

keep cropping up in my life, even as our ultra-portable wireless lives seemingly

allow us to feel at home anywhere in the world?

This question also underlies two issues in the headlines. As

the United States allows millions of illegal immigrants to functionally call

America their home, one wonders defines “home” and who gets to define who is at

home and who is “alien”. As Jerusalem is plunged back into violence and a deep

lack of personal security, the pat answer of home as a place of refuge and

safety is undermined. Strangely, despite the lack of security – the sense of

home goes unscathed, as it had in previous periods of fear. Home as safety is

an aspirational, but insufficient, answer. I am sent scurrying for other

definitions. This is where “A Bride for One Night: Talmudic Tales” by Ruth

Calderon found me. In her explorations of Talmudic narratives, she keeps

returning to stories focusing on the home, turning it into my recommended book

for this stormy month of Kislev.

Rav

Hama went and sat for twelve years in the study house. When he planned to

return home, he said “I will not do what Ben Hakinai did [and surprise my wife

after all these years]”.

He

stopped at the local House of Study and sent a letter to his wife.

His

son, Oshaya, came and sat before Rav Hama in the House of Study.

Rav

Hama did not recognize him.

Oshaya

asked him many questions of law. Rav Hama saw that he was a brilliant student,

and grew faint, thinking: “If I had stayed here, I could have had a son like

this.”

Finally

Rav Hama returned home. Oshaya entered behind him.

Rav

Hama stood before him, thinking: Surely this student is coming to ask me

another question of law.

His

wife scolded him: Does a father stand before his child? Do you not recognize

your own son?

(Babylonian

Talmud Ketubot 62b)

Seemingly a tale of a Rabbi over-zealous in his studies, so

lost in his Yeshiva he doesn’t recognize his own progeny, this story easily

evokes questions much closer to home. In our zeal for a professional life,

committed as we are to the demands of a successful career, do we find ourselves

not recognizing our own children as they grow up? 12 years or 100 hour weeks,

postponing family until one becomes Rosh Yeshiva/partner/tenured professor,

these questions are the clichéd conversations of our generation, and yet

balance alludes us. The Home and the House of Study compete – can we have it

all?

Rav Hama’s story is another version of the “treasure was at

home” tales, as in Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist or Reb Nachman’s tale of the

Treasure under the Bridge. Hama discovers that what he really wanted all along

was to have a son learned in Torah, not just to be a scholar himself. That son

was waiting for him at home all these years, ignored. Seemingly Hama has

attained both of these by the end of the tale – he is a great scholar, and so

is his son, Oshaya. He went on Odysseus’ journey and returned victorious. Yet

standing awkwardly in the kitchen, father and son face eachother in formality,

not intimacy. The journey was a failure if one is unrecognizable in your own

home.

This story captures the essence of home as being known,

familiar, comfortable, intimate. Home is where the guards can be put down,

where you don’t have to explain yourself, where one is understood. Hama lost

that familiarity with his son – and thus lost it with himself. “How much home

does a person need?” None, says young Hama, leaving for twelve years. Home is

where I am least understood, says the adolescent scholar, and goes. Only upon

returning home, a decade and more later, does he understand just how much “home”

was missed. The journey itself, the process of exile and return might be necessary,

but there is a limit: the journey away from home must end before alienation

sets in.

One post-script: The missing chapter about Rav Hama is the

one I am most curious about. Did he stay home? Did he rebuild his life at home,

or did the Yeshiva beckon him to return to his wanderings? The drama of return

often gets the headlines, but it is what we build once we’ve returned home that

is most challenging. That is the challenge we face today.

May this month of Kislev be a month of regaining home-hood:

being understood, feeling known, being safe.

Hodesh Tov,

Mishael

<Sidebar>

Barefoot Talmud

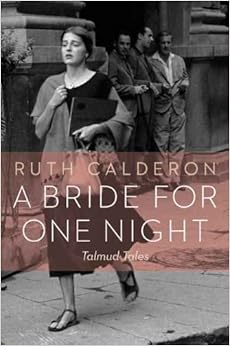

Ruth

Calderon, the public face of the new Jewish House of Study, even bringing Jewish text to the Israeli Knesset,

had her book of Talmudic stories come out in English this year. Aided by Ilana

A Bride

for one Night” Calderon takes 17 Talmudic tales, lays them out for the

reader to study themselves, then gives her own prose re-telling of the tale

before unpacking it more analytically. Rabbi Hama makes an appearance, as do

some other Bronfmanim favorites like Resh Lakish, Shimon bar Yohai and Elisha

ben Abuyah. It is the best book currently out there to recreate or share with others

the joy and passion of Jewish text study.

Ruth

Calderon, the public face of the new Jewish House of Study, even bringing Jewish text to the Israeli Knesset,

had her book of Talmudic stories come out in English this year. Aided by Ilana

A Bride

for one Night” Calderon takes 17 Talmudic tales, lays them out for the

reader to study themselves, then gives her own prose re-telling of the tale

before unpacking it more analytically. Rabbi Hama makes an appearance, as do

some other Bronfmanim favorites like Resh Lakish, Shimon bar Yohai and Elisha

ben Abuyah. It is the best book currently out there to recreate or share with others

the joy and passion of Jewish text study.

Dedicated to a theme in the Jewish month, Moonshine is a combination Dvar Torah and springboard for learning in the coming 30 days. Moonshine - in honor of the Hebrew month’s commitment to the lunar cycle, with a hint of distilling fine spirits off the beaten track and - perhaps - intoxication.