“What

is American Jews’ relationship to Israel?” is a topic of much debate,

discussion and handwringing in recent year. Words like crises, distancing,

occupation, religious freedom, BDS and assimilation often follow (though

usually not from the same people).

“What

is American Jews’ relationship to Israel?” is a topic of much debate,

discussion and handwringing in recent year. Words like crises, distancing,

occupation, religious freedom, BDS and assimilation often follow (though

usually not from the same people).

Leaving

the conversation at that question alone is a mistake. Two important questions

must be engaged more seriously: the touchier “What is American Jews’

relationship to Israelis?” and the all-but-ignored question: “What

is Israeli Jews’ relationship to American Jews?”

A

few weeks ago I was asked to speak at the first Wexner Alumni Summit on the topic of Stronger Together: [Re] Imagining the Israel-North American Jewish Community Relationship. My

(somewhat scary) job was to address these questions in front of a room of some

of Israel’s top civil servants and North America’s leading lay leaders. The

process helped me clarify in my own thinking how much these two communities

have contradicted and undermined each other from day one, and how they also need

each other and complement each other. I tried to pull apart the various debates

and arguments about whether American Jews’ are distancing from Israel and

Israelis, and to address head on the way Israelis never cared about American Jews’

and why this is changing today. I believe the tension between these two

communities is an important asset in ensuring the survival – or perhaps even the

flourishing: morally, spiritually, Jewishly - of these two strange and unique phenomenas

of Jewish history.

As

Israel celebrates its 68th year of existence I share my remarks

online, in a hope that some people still have patience to read something longer

than 800 word op-eds.

Intro One: A

Poem and a Seafaring metaphor

The poem was written some

600 years ago, by a French Jewish merchant who returned from from a business

trip in Germany, and spent Shabbat among the German Jews of Alsace. Deeply

disturbed by the type of Jews he met there, he eternalized his criticism in

meter and rhyme, writing the following poem. See if you can follow the Biblical

pun, which allows him to claim that “לא אלמן ישראל” - The Jews of Allemand are not part of Israel:

Anonymous (late Middle Ages?)

The Day That I Went Out from France

The day that I went out from France

And towards German lands made my advance

I found cruel people at first glance

Like ostriches in the wild plain

For Israel is not Alleman [=forsaken]

What has straw to do with grain?

I had hoped

to find salvation

A day of rest and relaxation

Yet their offerings lacked consideration

My heart was

cleft in twain

For Israel is not forsaken

What has straw to do with grain?

I searched

the breadth of all Alsace

No man knew its worth I came across

Oh, would that its ways were not such chaos —

Overriding men, the women reign

For Israel is not forsaken

What has straw to do with grain?

I’ve grown

utterly sick of Ashkenazim

For each one is fierce of face, I deem

Even their beards like goats’ beards seem

Heed not their words, all said in vain

For Israel is not forsaken

What has straw to do with grain?

|

משורר עלום שם

יום מצרפת יצאתי

יוֹם מִצָּרְפַת יָצָאתִי

אֶל אֶרֶץ אַשְׁכְּנַז יָרַדְתִּי

וְעַם אַכְזָר מָצָאתִי

כַּיְעֵנִים בַּמִּדְבָּר

כִּי לֹא אַלְמָן יִשְׂרָאֵל

מַה לַּתֶּבֶן אֶת הַבָּר?

צִפִּיתִי לִי לִישׁוּעָה

יוֹם נֹפֶשׁ וּמַרְגוֹעַ

וּמִנְחָתָם בְּלִי שָׁעָה

לְבָבִי הָיָה נִשְׁבָּר

כִּי לֹא אַלְמָן יִשְׂרָאֵל

מַה לַּתֶּבֶן אֶת הַבָּר?

חִפַּשְׂתִּי אֶלְזוּשׂ אָרְכָּהּ

וְלֹא יָדַע אֱנוֹשׁ עֶרְכָּהּ

לוּלֵי שֶֹלֹא כְּדַרְכָּהּ

הָאִשָּׁה עַל אִישׁ תִּגְבַּר

כִּי לֹא אַלְמָן יִשְׂרָאֵל

מַה לַּתֶּבֶן אֶת הַבָּר?

קַצְתִּי מְאֹד בְּאַשְׁכְּנַזִּים

כִּי הֵם כֻּלָּם פָּנִים עַזִּים

אַף זְקָנָם כְּמוֹ עִזִּים

אַל תַּאֲמֵן לָהֶם דָּבָר!

כִּי לֹא אַלְמָן יִשְׂרָאֵל

מַה לַּתֶּבֶן אֶת הַבָּר?

|

Even more so than the Jews of France and Germany, we live

in a time of two divergent Jewish communities. Can we envision a Jewish future

which is diverse, yet deep, divergent yet in dialogue –

between American and Israeli Jews?

Our poet is one

model, but when I think of a Jewish model for a healthy

|

| Kovner's Sea of Halakha |

relationship between

two communities, I think of the Talmud’s “Nehotei”. In the Sea of Talmudic

Halakha, the Nehotei (whose means literally “the descender”, or those

who “get down”) were the way-farers, the bold travelers who went back and forth

between Bavel and the Galilee, those two fabled centers of the Jewish Talmudic

world. They always transmitted what was going on in the other community. If you

follow their sayings closely, you realize their statements are usually game-changers.

Until they walk in, the whole discussion goes one way, but once they’ve

contributed their perspective, the debate goes in a whole new direction.

In many ways, you – the alumni of the various

Wexner leadership programs in Israel and North America, are a room of Nehotei

– each bringing ideas back and forth between the two communities. What we’ve

come together here to do is to become better Nehotei together.

Intro Two:

Patience, and lack thereof

We’re here to study “Talmud המביא לידי מעשה –learning that brings about action.” My job is to offer some

new frames for what we all already know, to give a shared language with which

we can shorthand our conversations; and to frame some of the machloket –

disagreements that perhaps exist in the room, and stir up the pot a bit so that

we can bring the power of this room to bear…

One disclaimer: I’m not the expert in

the room. People here have written books, led initiatives, organized mifgashim,

work full time or during ungodly hours after work towards these issues – some

of you have been doing this since before I was born. Instead my role here today

is to provide a scaffolding upon which we can rest the coming two days of

conversations.

Since I believe we learn best when we

discuss ourselves and not just listen, I’ve structured the second half of our

time together around three hevrutot

- 1:1 conversations with a pre-assigned partner, where we will ask three

questions:

- Who Cares?

Assessing this moment in Israeli-North

American Jewish relationship

- What are

“We”? Examining metaphors of connections between

the communities

- Going

Beyond Mifgash: Lessons Learned and Best Practices

But before we launch into the

conversation, wWe each have a story of how we became Nehotei – and I want to start

by briefly sharing with you mine:

I was born in Jerusalem –

but spent three years of elementary school in US public schools where I picked

up a wonderful American accent. I now work in a community that bridges both

communities, constantly going back and forth. But in preparation for this

summit, I realized that one pivotal moment in my story determined where I am

today.

Growing up in Israel, I saw the relationship between Israel

and America as a one-way street. Americans were great, but I mostly met them as

tourists in Israel, not in their home setting. Their job was to be the “good

uncle from Amerika” - support Israel financially and politically, buy Israeli

products and go home. Maybe their kids would make Aliyah (most would not), and

that would make me happy, but only if they shed their accent and funny clothes

and become “true Israelis.”

I come from a family that’s been going back and forth

between Israel and America since before the creation of the state. My

grandfather made Aliyah in 1947, and fought in the Hagana, before returning to

serve as a rabbi in Minneapolis for 25 years (a story that I told in this ELI

Talk called “A Tale of Two Zions”).

My father made Aliyah after 1967, and has trained a generation of teachers and

educators in both countries. Together we authored haggadot

in Hebrew and in English that have changed the way Jews in both countries

celebrate their Passover Seders, influenced how Jews in both countries tell

their key identity stories.

Until I realized that the things I thought that Israeli

society needed most could be learned from the American Jewish community, and

vice versa. This happened to me on both a national and personal level.

I had wanted to study to become a Rabbi for a few years – but was

displeased with the Israeli Orthodox training which only taught laws and not

leadership and community skills. I heard about a new Yeshiva which had opened

in New York – Chovevei Torah – and called up R Avi Weiss to ask if I could

apply. He rejected me, saying they trained Rabbis for the American Jewish

community, not the Israeli one. The rejection made me want to come even more.

“Teach me how to be an American community Rabbi – I’ll already do the

translating to the Israeli scene…” I said. My wife received a post-doc at

Columbia University, and we were on our way

But really what was going on was a desire to shake off israeli cynicism

that had set in; and a nagging feeling that encountering the American Jewish

community could teach me something valuable about being Israeli.

The summers of 2005-2006 were hard ones in Israel, The expulsion from

Gush Katif, the second Lebanon war hitting the following summer, we felt it was

hard to believe in big dreams anymore. My wife and I realized we wanted to

travel to America to drink up some of the koolaid of American naiveté, of the

belief in “Tikkun Olam”, seeking a place where we can dream again – but not as

a turning of our backs on Israel, but as a way to return to Israel.

What we always found funny was how we were constantly asked to choose

sides. “You’re coming back, right” – the bookseller at the second hand book store

in Jerusalem demanded before taking my books. “So you’ve chosen Israel over

us?” asked our friends at our Upper West Side synagogue when we left New York;

“תגידו את האמת, איפה יותר טוב?”

– “Tell me the truth, where is it better?” demanded that passport woman at Ben

Gurion…

So before we go any further, I want – with your permission – to say a few

things I have no patience for in this conversation: I have very little patience

for the either/or mentality of Israel versus North America; for the “where is it better” insecurities, for

the competition to see “who will be the first to fail”. I have very little

patience for the way people in both communities project unto the other one that

everything is either “great” or “horrible” about the other community (or about

their own ); I have very little patience for awkward “mifgashim”, for sticky

talk of “peoplehood” and for “we are one” fluffiness, for the superiority

complex of liberaler-than-thou Americans and the hubris of macho Israelis who know

what “real” danger and sacrifice are like.

I could go on, but here are some things I do have patience

for: I have patience for these two far-from-perfect communities, this

dysfunctional family with a tendency for self-delusion, to develop their

discord into the amazing machloket that it could be, to find the ways in

which we can learn from each other and teach eachother – and make the most of

this unique moment in Jewish history.

The “Jewish Normal” Living in Generations of Rapid change

|

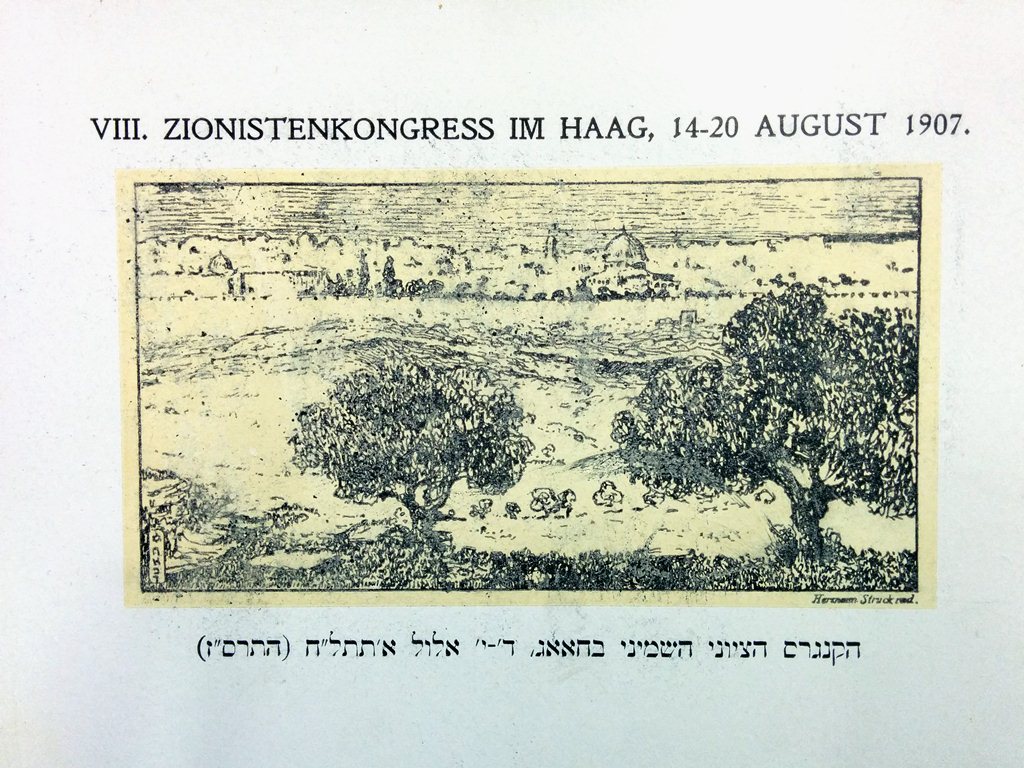

| Invite to the 8th Zionist Congress in the Hague, 1907 |

Just over 100 years ago, summer of 1907, in the tiny town of Eibergen

(Dutch for Eggtown) a curious Manuel Zion, my great-grandfather, rides his

horse and buggy from his small Dutch town to the Hague. He had heard that the

8th Zionist Congress was to take place in the city, and since he carried the

unusual name of “Zion” he decided to find out what all this Zionisten thing was

about.

When he returned home to Eibergen, excited if skeptical of

the grand ideas and programs that were thrown back and forth in that room, he

finds a letter: “You are hereby disinvited from the Jewish community’s dinner

and dance – there will be no place in our community for Zionists.”

I think of this story often when I am looking for some

context about how we got here and where we might be 100 years from now. Sometimes

the best thing you can do is to get disinvited from the community dinner and

dance on the way to a grander vision.

I’ll bet each one of us in this room has a “Manuel Zion’s story” of

some kind in our ancestry, not too many generations back. These stories serve as

a reminder that there is nothing “normal” about Jewish existence today. In

fact, what i s so un-normal

is how “normal” everything feels to those of us born into these realities.

There is so much we take for granted which was not even imaginable for our

ancestors.

1848 – 11 million Jews, of which less than 100,000 Jews

live in Israel or America

1939 – 17 million Jews

1948 – Back at 11 million, but a Jewish state is

founded by less than 7% of the Jewish people; meanwhile – a third of the Jewish

people live in America;

2016 – 40% in each country, 20% in the rest of the

world

2050 - projections of 8 million Jews in Israel,

steady 6 million Jews in US?

So this is all very new. I say this to caution us against

doomsday predictability scenarios, and also to inspire hope that paradigms

shift and change, pendulums swing and social initiatives do matter (although

perhaps not as much as social, economic and political factors).

Two

Homes: Different, Contradictory or Complimentary?

There is one very important characteristic that is shared by the 2

communities that are the majorityof the Jewish people, and which differentiates

us from the other 20% of World Jewry:

both communities are very much at home, both have arrived.

That in itself is not your “Jewish normal”. If the ongoing dichotomy of

Jewish existence has been exile or redemption, we now face a third option: arrival.

It is not quite the messianic redemption, but it definitely feels like a final destination.

In both Israel and America, a majority of the Jewish people feel that they are

“at home” in the country in which they reside. And I believe that fundamentally

understanding how “at home” the Jewish people are in the two homes, their two

“Zions”, is extremely important to reframing the work between the two

communities. You might not agree with me on this point, or you might feel that

this is exactly where the problem lies. But questioning the assumptions of

various Jews on “where home is” is exactly the place where I believe the

conversation should start, for our two homes are extremely different from eachother:

Lets count the ways:

1. Languages:

the two communities speak different languagues, Hebrew and English, ont only as

their day-to-day language, but as their Jewish language. A person can be

considered wholly literate without knowing much of the other communities

literary cannon.

2. They define their Jewish

lives very differently – the two largest groups in each community define

their Jewish lives very differently, even if their practice is relatively

similar: Reform/Conservative in North America vs. Hiloni/Masorti in Israel;

this also means that the Haredi and Dati/MO groups in both communities find it

easier to be together than the other groups, and are more often those more

concerned about the relationship.

3. Political views are viewed

very differently: a majority of US jews are left/liberal, majority of Israeli

jews are center and right (left is a brand in severe crises in Israel); they

view issues of settlements and attempt towards peace very differently;

4. The basic organizing ethic

of the two communities is very different: Israel is based in a culture of

obligation – מצווה, שוויוןי בנטל, אין ברירה while American

Jewish community is voluntaristic – both as a practice and as an ethic. This is

not a judgement, but an observation – it effects where power lies: think of the

type of leadership in this room – civil servants vs. volunteer lay leaders… The Wexner Foundation mode of identifying the

core leadership in each country led to very different paths, because the power

and prestige lies in two very different forms of service.

5. Separate base experiences

are different: ongoing threat vs. prosperity and gratitude

a. Neighborhoods:

Middle East/North America – Jews in

Israel aer the majority, but in their neighborhood they feel like the “Middle

Eastern other” in a way that recapitulates us being the European “other” for so

many centuries. But in the US, Jews are not the other, but in fact, mostly

white and privileged. They are accepted as being part of the majority, yet have

a self-understanding of themselves as a minority.

6. Most interestingly, Israeli

and North American Jews view the threats to Israeli life very differently. 39%

of Israelis think the most important long-term problem facing Israel is

economic problems. American Jews – 1%. (Do any Americans recognize the name Guy

Rolnik or read “The Marker”?)

Either way, it thus makes sense that the “relationship” between

these two communities should be so fraught, simply because of the huge

differences between them. And yet we are

not simply two “different” communities, we are actually two contradictory

Jewish projects that by their very nature repudiate eachother:

a. The Israeli project is

about creating a Jewish “State”; its underlying assumption is that Jews will only be safe if living on their own

land and organized politically. The project includes redefining what Jewish means – Judaism exists primarily in the public space; and for generation the

project also included Judaism being super-ceded by Israeliness, weakening the

tie to non-Israeli Jews. Its central challenge is that of being the majority.

It’s blessing is also a cruse: the unique challenge of power being colored

“Jewish”: maintaining a Jewish military, Jewish sovereignty, a Jewish foreign

policy…

b. The North American

project on the other hand has a very different kind of power. It’s central goal

is proving that a prosperous Jewish Diaspora is possible, that we can be a safe

and vibrant minority within a democracy which is truly welcoming of minorities.

The success of North American Jews disproves Herzlian Zionism on a daily basis –

Jews can indeed live safely while being a minority. The energy of the project

seemingly is that of remaining Jewish – but really the project is that of being

American, and ensuring the America is welcoming to minorities such as

ourselves. Jews came to America and discovered they are not only good at

becoming Americans, they are good at telling Americans what the American story

actually is (and if Jewish helps that, great).

In these ways and others, these two

projects undermine eachother, but perhaps they are also complimentary –

perhaps each community is only possible because of the other community? perhaps

ONLY POSSIBLE because of the other community?

Would Jews be allowed to live in

Westchester NY if not for the Jewish state? Would Israel have American support

if not for the organized Jewish community?

Can this implicit complementariness, played out in social and political

currency, also become an overt one, in a mutual exchange of ideas?

Returning

to the Origins of the Relationship: The Blaustein-Ben Gurion Agreement

|

| Ben Gurion, Blaustein and Golda Meir, 1950 |

Before

we examine the various answers given in your applications to these questions,

I’d like to return to one of the seminal

moments of the relationship between the two communities, as it shows that it

was always a fraught one. On August 23, 1950, on invitation of Prime Minister

David Ben Gurion, the President of the American Jewish Committee and US

industrialist Jacob Blaustein visited Israel.The Prime Minister and Mr. Blaustein

issued statements expressing their mutual understanding about the relationship.

We must remember that at the time, Americans supplied about 30% of Israel’s GDP,

so its not clear how beholden Ben Gurion felt to Blaustein:

David

Ben Gurion: The Jews of the United States, as a community and as

individuals, have only one political attachment and that is to the United

States of America. They owe no political allegiance to Israel. The State of

Israel represents and speaks only on behalf of its own citizens, and in no way

presumes to represent or speak in the name of the Jews who are citizens of any

other country. We, the people of Israel, have no desire and no intention to

interfere in any way with the internal affairs of Jewish communities abroad.

The Government and the people of Israel fully respect the right and integrity

of the Jewish com munities

in other countries to develop their own mode of life and their indigenous

social, economic and cultural institutions in accordance with their own needs

and aspirations.

Jacob

Blaustein: We shall do all we can to increase further our share in the great

historic task of helping Israel to solve its problems and develop as a free,

independent and flourishing democracy… But Israel also has a responsibility in

this situation — a responsibility in terms of not affecting adversely the

sensibilities of Jews who are citizens of other states by what it says or does.

American Jews vigorously repudiate any suggestion or implication that they are

in exile. American Jews — young and old alike, Zionists and non-Zionists alike

— are profoundly attached to America.

To

American Jews, America is home. There, exist their thriving roots; there, is

the country which they have helped to build; and there, they share its fruits

and its destiny. They believe in the future of a democratic society in the

United States under which all citizens, irrespective of creed or race, can live

on terms of equality. They further believe that, if democracy should fail in

America, there would be no future for democracy anywhere in the world, and that

the very existence of an independent State of Israel would be problematic.

Further, they feel that a world in which it would be possible for Jews to be

driven by persecution from America would not be a world safe for Israel either;

indeed it is hard to conceive how it would be a world safe for any human being.

Yet a few years after these statements, Ben Gurion was

found back to his previopus antics, undermining the legitimacy of the North

American Jewish community:

In

his address to the World Zionist Congress in December 1960, Ben Gurion

declared: “Since the day when the Jewish state was established and the gates

of Israel were flung open to every Jew who wanted to come, every religious Jew

has daily violated the precepts of Judaism and the Torah by remaining in the

Diaspora. Whoever dwells outside the land of Israel is considered to have no

God, the sages said… In several totalitarian and Moslem countries, Judaism is

in danger of death by strangulation; in the free and prosperous countries it

faces death by a kiss — a slow and imperceptible decline into the abyss of

assimilation.”

The same tones heard today – a sense of mutual undermining,

a threat of assimilation versus that of dual loyalty, a myth of possible distancing,

declarations of co-dependency alongside “get off my turf”-ness, where there from

the begininng.

Then why is there a current sense of crises, and where does

it emanate from? Many

of you wrote about a crises in your applications, but you disagreed on what the

crises is. I’d like to share a few of the machlokot that exist in this room

(and in the wider world):

Let's

start with the North American perspective. Many claim that there is “Distancing”

– that a younger generation doesn’t care about Israel as much as their parents

did. If

it exists, why? And is it a bad thing, or perhaps a good one?

1.

Seminal memories –

the generational gap emanates from very different seminal memories: not the

Israel of 1967 which re-shaped the way in which American Jews saw

themselves. Israel is experienced not as a confidence booster to American Jews,

but as a liability.

2.

This in large part has to

do with differing views over the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.

o

Majority of American Jews

blame Israeli Policy for the current situation and resent Israeli leadership that

is cynical about peace efforts. This generation doesn’t remember 1967 or 1994,

but a local superpower fighting against guerilla warfare and local uprisings.

o

Israeli majority feels

stalemated: it supports a two-state solution on paper but doesn’t believe it is

possible to achieve. Israeli society is swerving to the right, with the left

crumbling and the seminal memories of move people under 30 is of ongoing

Intifada.

3.

An opposite reading – also

heard loud and clear in the applications - sees the distancing of young people from

Israel as the result of a campaign and a broad sentiment on college

campuses, BDS initiatives and the bundling of various other progressive

agendas with the anti-Israel cause.

4.

A different approach

locates the challenge in the lack of religious Pluralism and freedom in

Israel. In the American Jewish community, where the Reform movement makes

up the largest denomination, and core American values are also seen as core

Jewish values – pluralism, religious tolerance and freedom of religion –it is

hard to get excited about an Israel in which women can be arrested for reading

Torah at the Kotel or where their Judaism is not recognized.

5.

The flip side of this

argument can be seen in the claim that it is the rampant assimilation in

America which is the problem and the greatest threat to the relationship. The “vanishing

American Jew” that has also disconnected from values of Jewish solidarity and

obligation is eroding the bond between Israel and America

But this has been from an America-centric perspective. What

happens when we look at distancing of Israeli Jews from American Jews? Not

a myth of a better time, but an understanding that Israelis never quite knew

what to do with American Jews.

Hebrew identity – erasing previous identity; Negation of the

Diaspora – AB Yehoshua as a paradigm: diaspora is a neurosis, an unhealthy

split personality; only way to be full Jew is in Israel.

What gets headlines in Israel is “Vanishing American Jews” –

which fits the paradigm mentioned in Ben Gurion’s 1960 quote above. What

Israelis think of Americans is: דוד מאמריקה (Uncle from America); Aipac supporters, רפורמים

(“Reformim”) = “weird Jews”; תיירי תגלית (birthright tourists). They hardly ever

get to encounter American Jews “at home” and thus never understand their ethos,

communities and lives in context.

When

do Israelis learn about Diaspora Judaism? In Poland! Israeli Education about

Diaspora Judaism is state-sponsored Poland trips – and despite many exchanges,

the over-arching frame of Auschwitz or IDF continues to be a powerful frame.

The challenge to my mind is that both communities seem to

assume an Israel-centric frame.

What caused this frame is that while in 1948, American Jews

like Blaustein perceived themselves to be at home in American, in 1967 Israel’s

amazing feat allowed American Jews to feel more at home in America than ever

before. As Boston’s CJP President Bary Schrage put it: Until 1967, I would

often be called a “yellow, little Jew” on my way to school in Brooklyn. After

June 1967, that never happened again. Israel saved American Jewish identity

once in 1967, and in some people’s mind, its doing that again today, with

Birthright.

Yet on the other hand, since 1977 Israel stopped being

“David” and to some it became “Goliath”. Israel’s success as a modern economy

and a “StartUpNation” meant that it mostly outgrew the need for financial aid

from the American Jewish community.

2015: Year of Realignment?

On a strategic level, over the last twenty years we’ve seen

a significant shift in the way the relationship works. If in the past

the expectation was that American Jews lend their financial capital to

Israel, increasingly American Jews are using their political capital to

get their government to support Israel.

This has met with much success, but recently was pushed to

the limit when the PM of Israel expected to see both political and communal

Jewish institutions bend their support against a sitting president. There are

many ways to tell this story, but it represents a watershed moment, as it brings

back the old challenge of Jacob Blaustein – that of dual loyalty.

At the same time, we’re seeing American Jews becoming more unabashedly

interventionist in Israeli society. The most popular newspaper in Israel is

owned by an American Jewish billionaire with a very clear political agenda.

Organizations like the NIF on the left and Elad on the right raise US funds to

further their vision for how Israel should look.

Most recently, the Federation system and the AJC have

swung their support towards political endeavors relating to freedom of religion

in Israel. On the other end, the minister of Diaspora Affairs has been seeking

to lead a major initiative about the Jewish identity of North American Jews –

and to overthrow the Jewish Agency’s power over Diaspora politics.

There are new trends, showing a tectonic shift that is not

only of distancing, but of growing closeness and intervention in the other

community.

-

Many young Americans are

distancing from Israel at a rapid rate, while many other Americans want to

celebrate their Symbolic Particularism in Israel. Yet by doing so they are

undermining the liberal values that 70% of them believe in. as long as American

Jews feel more at home in Israel than Arab citizens of Israel, we are weakening

Israel as a democracy. The Law of Return seems to be getting in the way. On the

other hand recently we’ve seen a rise in awareness of the American Jewish

community: women of the wall, the Federations stepping up; issues of Jewish pluralism

being tied to lending political support to Israel.

-

Many Israelis still need to

believe it’s Auschwitz or Tel Aviv, not NYC. On the other hand, hundreds of

thousands of Israelis are living or have lived in North America, and have a

renwed appreciation of the value of American Jewish life.

So the dyanmics of the relationship are not as simple as one

of “distancing”, and never have been. Rather, there is a distancing of some and

an intervention and closeness on the other hand.

I order to better effect this relationship, and understand

its effect on us, we must also examine the words and metaphors we use in

reference to it.

Many of you mentioned the need for a new covenant, a new

paradigm. Words like partnership, non-utilitarian relationship, family, and “we

need to decide to be one people.”

Metaphors have power. Each metaphor is a theory of change,

it’s a strategy, implies an ethic. Being mindful of these metaphors is

important.

I leave you with four questions:

1. How do we build a mutually generative relationship between two

“arrived” communities that have divergent and contradictory Jewish experiences?

2. What are the tipping points, pressure points, bridges,

disruptors and translators needed for such a relationship?

3. What method should be embraced: popular connection, leadership

to leadership, peer to peer?

4. What are the current assets, challenges and future trends that

should be taken into account?

Ending: Jewish People in Bundles

There is often much talk of a need for unity, yet I believe,

like Yishayahu Leibowitz, that “No good idea ever came out of a call for

unity”. Rather, a rigorous debate, an awareness of our differences, and the

ability to leverage those differences in order to strengthen the connections

between us, is what we aer called to do. The following Midrash displays this

tension with a unqie metaphor. Do we want to build one ship, or do we want to

tie many small boats together?

"ויהי בישרון מלך בהתאסף ראשי עם יחד שבטי ישראל"

(דברים לג:ה)

כשהם עשוים אגודה אחת , ולא

כשהם עשוים אגודות אגודות

וכן הוא אומר "הבונה

בשמים מעלותיו ואגודתו על ארץ יסדה" (עמוס ט:ו).

רבי שמעון בן יוחי אומר:

משל לאחד שהביא שתי ספינות וקשרם בהוגנים ובעשתות והעמידן בלב הים ובנה עליהם

פלטרין כל זמן שהספינות קשורות זו בזו פלטרין קיימים פרשו ספינות אין פלטרין

קיימים כך ישראל כשעושים רצונו של מקום בונה עליותיו בשמים וכשאין עושים רצונו

כביכול אגודתו על ארץ יסדה.

|

“The LORD became king in Israel--when the

leaders of the people assembled, when the tribes of Israel gathered as one”

(Deutoronomy 33:5) – When they are gathered as one bundle, and not when they

are divided into bundles and bundles, and so says the verse: “He who builds

his upper chambers in the heavens and founds His bundle upon the earth” (Amos

9:6).

Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai says: This is like

a person who brought two ships and anchored them together and placed them in

the middle of the sea and built upon them a palace. As long as the ships are

tied to eachother – the palace exists. Once the ships separate from eachother

– the palaces cannot exist.

So are Israel – when they are fulfilling

the will of the Omnipresent – “He who builds his upper chambers in the

heavens”, and when they are not fulfilling his will – it is as if “His bundle

is upon the earth”.

|

As the seafaring “Nehotei” that we are, we each ride very

different ships. Trying to turn them into one boat would be a bad idea. Rather,

if we can – like Shimon Bar Yochai suggests – tie many boats together, then we

will find ourselves living within a much richer – and stronger – two

communities. The waters are treacherous, lets hope this way we can ride out the

current storms… and perhaps kick up some new ones.