Rav Yehuda said: One who wishes to be a Hasid

must fulfill the matters of Damages [Nezikin].

Ravina said: One who wishes to be a Hasid must fulfill the

matters of the Fathers [Ethics of the Fathers, Pirkei Avot].

Others said: One who wishes to be a Hasid must fulfill the

matters of Blessings [Berakhot].

Babylonian Talmud, Bava Kama 30a

Leading a virtuous life. Does anyone wonder about that anymore? Not the

satisfying life, or the happy life;

nor the life

of impact. The Talmud asks a question about virtue, indeed of heroic

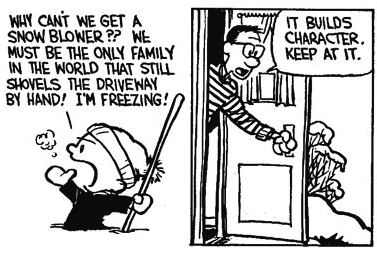

virtue: How does one become a Hassid. Or as Calvin’s dad

would put it: how best to build character?

Leading a virtuous life. Does anyone wonder about that anymore? Not the

satisfying life, or the happy life;

nor the life

of impact. The Talmud asks a question about virtue, indeed of heroic

virtue: How does one become a Hassid. Or as Calvin’s dad

would put it: how best to build character?

To be fair, that is not how most people would translate the word Hasid.

Hasid is often reduced to “pious”, meaning “deeply religious : devoted

to a particular religion” according to Merriam-Webster, or “a combination of fervor and devotion to God”.

The term Hasid has been repeatedly reborn over the course of Jewish

history. From the Hasidim dancing ecstatically at the Temple (1st C),

to the prostrating Sufi Jews of Cairo (13th C), the Franciscan style

Hasidim of Germany (13th C) and the spiritual revolutionaries of

Eastern Europe (18th C). And then of course there are our

contemporaries, who seem to share a preference for black

clothes and facial hair, and the neo-Hasid’s who prefer colorful tallitot and

shamanic chants.

Despite this rich history, most people assume Hasid=Pious,

a term which, as Google shows, gets very little traction these days. Indeed, the second

definition for pious offered by Webster’s is “falsely appearing to be

good or moral”. Thankfully, this Talmudic argument invites us to redefine

Hasid.

To be fair, the third answer offered above fits expectations most easily: “One who wishes to be a Hasid must

fulfill the matters of Blessings [Berakhot]”. Berakhot, the tractate

educating in the laws of prayer and blessings, implies that being a Hasid

relates first of all to spirituality and gratitude. It is primarily about

vertical relationships: God/Man. Indeed, the Mishna tells us that “The pious of former generations used to contemplate

for one hour before they would begin prayer.” – which opens a window into ancient Jewish

Meditation (I always saw those Hasidim as the ones who are to blame for Jewish

prayer sprawling for hours and hours). To be sure, there is a strong

argument to be made that a person well versed in the ethics of gratitude,

investing time and effort in deepening a spiritual practice, would be setting to foundations of becoming a Hasid.

A very different definition of Hasid is evoked by Ravina’s position:

“One who wishes to be a Hasid

must fulfill the matters of the Fathers”. Ravina is probably referring to

the Tractate of Mishna often called “Ethics of the Fathers”, Pirkei Avot.

Avot fits into the category of “wisdom books” known across

civilizations, from the biblical Proverbs to Tao Te Ching: short prescriptive

aphorisms that shape behavior and world view. Avot recognizes that there

is the “medium” personality and the

Donors fall into four types:

Those who wish to give and others not give – they rob

others of merit.

Those who urge others to give but do not give themselves –

they rob themselves of merit.

Those who give and urge others to give – those are the

Hasidim.

Those who do not give and urge others not to give – these

are the wicked. (Avot 5:16)

Where Berakhot is mostly a vertical, God/self relationship, Avot weaves a

combination of vertical and horizontal God/other/self. If the Hasid of Berakhot

is pious, the Hasid of Avot is ethical – if such distinctions can be

made. Yet for all of its inspiring messages, Pirkei Avot takes place in

a vaccum. It assumes that ethical behavior emanates simply from the individual,

but does not account for the complex realities of interpersonal conflict, the pervasiveness

of mistakes or the gray areas of moral decisions.

Which brings us

back to the first and most counter-intuitive statement: “Rav Yehudah

said: One who wishes to be a Hasid must fulfill the matters

of Damages [Nezikin].” The Tractate of Damages

(today consisting of three separate “gates” – Bava Kamma, Bava Metzia and Bava Batra)

covers 30 chapters of torts and contract law.. What do the ins and outs of

financial compensation have to do with being a Hasid? Well, everything.

Where the words of Avot discuss the ideal person leading the ideal life,

the Tractate of Damages takes the opposite approach: human beings – and their

animals, belongings and agreements – are liabilities waiting to happen. When

living in a society mistakes, losses and damages will occur. The challenge is

how to fix things. This is not about ideal justice but rather about regaining

balance in a broken world. It will never be whole, it will never return to the

original state. One who can maneuver skillfully in such a world is a Hassid.

The centrality of the Laws of Damages to Jewish discourse is clear from

their location in this week’s Torah portion, Mishpatim, directly after

the giving of the Torah at Sinai. To this day traditional Jewish Talmudic education

for children begins with the rules relating to lost property – which “findings”

belongs to you vs those for which you are responsible to seek out the owner, even

though you have no idea who he is. One who wishes to raise a Hasid, first teach

them that “Finders keepers, losers weepers” is wrong.

In order to administer the laws of damages properly, one needs to become

deeply versed in human needs – physical and psychological. Damages educates one

to embrace the perspective of the other, while constantly keeping an eye on the

global good (the discussion of Ken

Feinberg, damage compensation guru, reflects this point well - thank you

Zach Luck for this connection!).

In Damages, as in Avot and Berakhot, there is the “average behavior” and then

there are the Hasidim, who accept a higher bar of responsibility, a path of

higher virtue. Right before our argument about the correct path to becoming a Hasid,

the Talmud gives the following anecdote:

Our Rabbis taught: The Hasidim of

former generations used to pick up thorns and broken glasses [from the public

sphere] and bury them in the midst of their own fields, at a depth of three

handbreadths below the surface so that the plough might not be hindered by

them.

Rav Sheshet used to throw them into the fire.

Rava threw them into the Tigris river. (Babylonian Talmud, Bava Kama 30a)

Waste management is where societies’ values are tested, as the news from West Virginia showed us this week. As we know from

environmental studies, waste management is not just about the vertical

(God/man), or the horizontal (man/others), it is also about the future

(now/later). Most significantly, the Hasid sees the public square as her personal

responsibility, even at a cost to her own property. This deeper view of the

public domain reflects a flipping of the common instinctual private property

perspective (upon which our glorious nation is founded). In the common

understanding, what is mine is mine, and communal space is very questionably

mine. Since responsibility for it is shared, personal responsibility is highly

diminished. The Hasidim stand this idea on its head. Another example of the

Hasid of Damages reflects this position well:

|

Our masters taught:

One should not clear stones out of

one's own domain and throw them into the public domain.

Once a man was clearing stones out of

his own domain and throwing them into the public domain.

A Hasid saw him and said:

“Empty One, why do you remove stones

from a domain that is not yours to a domain that is yours?”

The man just laughed at him.

After a time, the man was forced to

sell his field, and, walking on that very public domain, he stumbled over the

stones he had thrown.

He said, “How well that pious man put

it: ‘Why do you remove stones from a domain that is not yours to a domain

that is yours?’”

Bava Kamma 50b

|

ת"ר: לא יסקל אדם

מרשותו לרה"ר.

מעשה באדם אחד שהיה

מסקל מרשותו לרה"ר,

ומצאו חסיד אחד,

אמר לו: ריקה, מפני מה

אתה מסקל מרשות שאינה שלך לרשות שלך!

לגלג עליו.

לימים נצרך למכור שדהו,

והיה מהלך באותו רשות הרבים ונכשל באותן אבנים,

אמר: יפה אמר לי אותו

חסיד "מפני

מה אתה מסקל מרשות שאינה שלך לרשות שלך"...

|

May this week be a calling for us to redefine not only where “our domain”

is, but also what the term Hasid can inspire in our lives. Few of us

might achieve that status, but at least it is something to aspire to.

Shabbat shalom,

Mishael