Offered in prayer for

the well-being and return home of teenagers Eyal Yifrah, Gilad Shaar and Naftali

Frenkel, and for the better handling of arguments in the world.

Once again, we live in a

time of growing dispute and polarization. The political discourse is

increasingly toxic, and instead of engaging in a deeper exchange, disagreeable

ideas are tarred and fathered, labelled as outside the camp and intolerable. With one's back against the wall, it feels almost impossible to extend the other side the benefit of the doubt or find any sense in the arguments coming from across

the aisle. It would be so much more convenient if the earth simply opened its

mouth and swallowed up the opposition.

Once again, we live in a

time of growing dispute and polarization. The political discourse is

increasingly toxic, and instead of engaging in a deeper exchange, disagreeable

ideas are tarred and fathered, labelled as outside the camp and intolerable. With one's back against the wall, it feels almost impossible to extend the other side the benefit of the doubt or find any sense in the arguments coming from across

the aisle. It would be so much more convenient if the earth simply opened its

mouth and swallowed up the opposition.

This is the fate of the

opposition described in this week’s Torah portion, Korah. In the heat of the

desert, banned from entering the land until an entire generation dies, the

Israelites mount a rebellion against Moshe and Aaron’s leadership. Led by Moshe’s

cousin Korah and 250 irked chieftains, the rebellion is quashed in a series of

miraculous acts, the first of which occurs when the earth swallows the rebels,

tents and all. Famously, Korah’s mutiny becomes the archetype of the

illegitimate argument in Jewish thought:

An

argument for the sake of Heaven will endure;

But

an argument not for the sake of Heaven will not endure.

Which

is an argument for the sake of Heaven? The arguments of Hillel and Shammai.

Which

is an argument not for the sake of Heaven? The argument of Korach and his

company.

(Mishna Pirkei Avot/Ethics of the

Fathers 5:17)

Yet, how does one know

when an argument is for the sake of Heaven? Almost any argument can be viewed

through the cynical lens of self-promotion (as we too often reduce politics to)

or aggrandized to be about philosophical ideals and altruistic motives. Hasn’t

Korach’s argument itself endured, eternalized by becoming the archetype of

arguments that aren’t for the sake of Heaven?

|

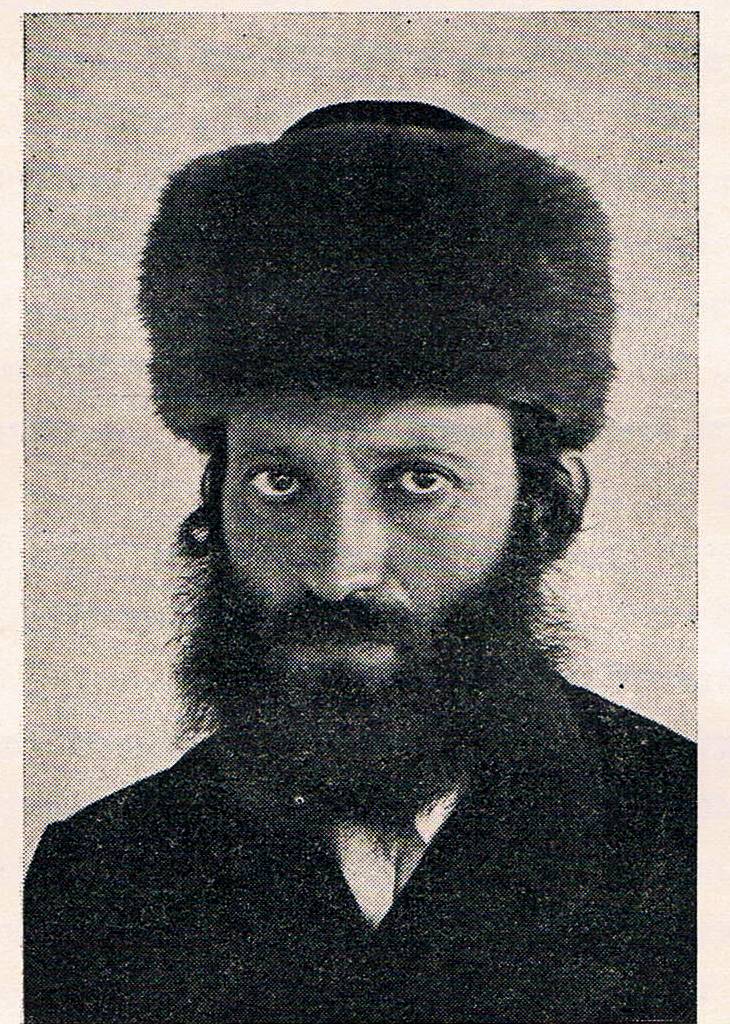

| Rav Kook, 1888 |

Faced with this question,

I reflect back on a letter written by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook to his brother

Shmuel in 1910. It contains a sweet story of brotherly love: Arriving in Jaffa,

Rav Kook finds himself serving as the Orthodox rabbi of the resoundingly

secular Pioneers of the Land of Israel. His faith in their work and support of them pitted him against the old world Orthodox leadership of Jerusalem, who labeled him a traitor to Jewish Law and Tradition. The argument became toxic when Kook justified a lenient ruling allowing the farming of the Land of Israel during the Sabbatical (Shmitta) year. Kook sought to effectively allow

the secular Jewish farmers to continue to till the Holy Land, despite the

Biblical declaration that once every seven years all agricultural work must be

stopped and the land must be allowed to rest. His arguments were laid out in a

small pamphlet called Shabbat ha’Aretz , “The Land’s Sabbath”, which he

proudly sent home to his supportive brother Shmuel back in Lithuania. In

Jerusalem’s Old City the book was not received with the same excitement, to say

the least. A vehement personal attack of Rav Kook was launched. Back in Lithuania Shmuel wrote to Kook to express his poor opinion the old guard attackers. Rav Kook’s response reveals a surprisingly measured and ever

relevant perspective about such disputes:

Jaffa, 1910

Shmuel, my beloved brother,

While your words are true and said in the spirit of justice and pure faith,

it nevertheless behooves us to constantly expand our horizons, and to give

every person the benefit of the doubt (Pirkei Avot 1:6). Even to those on a distant and undecipherable path!

We must never forget that in every battle waged in the war of ideas, once the

initial agitation subsides –lights and shadows can be found on both sides of

the argument.

Indeed by attunement to Divine will we know that all human action and ideas

in the world - large and small - are set and arranged by the One who Reads All

Generations, to improve the world and brings about progress, to increase light

and stamp out darkness. And even as we battle in fervor for those issues that

are closest to our heart, we must not give in to our emotions. Rather we must

always keep in mind that even those sentiments opposite to ours – have a wide

place in the world, and that “the God who gives breath to all flesh” (Numbers 27:16) “has made everything beautiful for its time” (Kohelet 3:11).

This perspective must never stop us from fighting for that which is sacred,

true and dear to us. However it can help us from falling into the net of small

mindedness, contempt and irascibility. And may we instead be full of courage,

serenity and faith in the God who loves Truth, who will not forsake his

followers.

I would be most pleased if you use any opportunity which comes your way to

exert your influence, quiet the spirits and increase mutual respect in your

circles, as is fitting for people of integrity and wisdom, who know their own

virtue and objective as clearly as daylight.

(Letters of Rav Kook, I:314)

Rav Kook does not question

the motivations of his opponents, seeking to distinguish between “arguments for

the sake of Heaven” and those which are not. Rather, he claims that all arguments

are for the “sake of Heaven”, inasmuch as they eventually play a role in “improving

the world and bringing about progress,

|

| A Letter by Rav Kook, from his Jerusalem years |

Kook’s position is rooted

in a modernist and mystical faith in the ongoing progress of the world. Yet it

can still be valuable to those of us more cynical of modernist progress, or doubtful

of a detailed mystical plans. In an age of polarization on one hand and

relativism on the other, instead of seeking to push our opponents down into the

bowels of the earth, we must hold onto two truths at once: that we can fight

for what we believe in without falling into relativism, that we can believe in

our own justice even as we respect those on the other side. As Kook urges his

kid brother Shmuel, that is the only fitting way for someone who seeks to live

a life of both virtue and integrity.

Shabbat Shalom,

Mishael

p.s. an English edition of Shabbat HaAretz's Introduction, arguably the most important work of Jewish environmental spirituality is forthcoming from Hazon in honor of the upcoming Shmitta year of 2014-2015 and I'm looking forward to reading it. I'm also looking forward to reading the new biography of Rabbi Kook by Yehuda Mirsky sometime this summer...