It’s

been a tough fortnight: Last week, a US soldier, SSgt Bales, sent to Afghanistan

by my country, cold bloodedly massacred 16 Afghanis in their homes. This week a

French Al Qaeda supporter cold bloodedly killed 4 of my people, of them 3

children. These two acts sear the mind and break the heart. Horror, shame, grief

and fear have been coursing through the heart this week. Out of those emotions,

though, ethical questions are raised: Do I bear a modicum of responsibility for

the actions of SSgt Bales? Do the deaths of French citizens I have never met relate

to me more than other deaths this week?

Cast

largely, these events raise the basic questions of solidarity and collectivity:

Towards

whom do I owe collective responsibility? Regarding whom do I feel collective

grief? In other words: who is my we?

Turning

to the Parasha to serve as a sounding board for these questions, one might be

disheartened: it is the opening of the book of VaYikra (Leviticus), that antiquated

collection of priestly laws. But “Blessed is the Lord who gave us Torah, and who

gave us Scholars to interpret it”, for Prof. Jacob Milgrom, the pre-eminent

scholar of Leviticus, comes to the rescue. As a teenager in Jerusalem, I used

to fix Prof. Milgrom’s Commodore 64 computer. He in exchange would teach me

VaYikra.

For

Milgrom:

Values are what Leviticus is all about. They pervade every chapter

and almost every verse. Underlying the rituals, the careful reader will find an

intricate web of values that purports to model how we should relate to God and

to one another.

Anthropology has taught us that when a society wishes to express

and preserve its basic values, it ensconces them in rituals. How logical! Words

fall from our lips like the dead leaves of autumn, but rituals endure with

repetition. They are visual and participatory. They embed themselves in memory

at a young age, reinforced with each enactment. (Introduction to Leviticus:

A Continental Commentary)

Using

our knowledge of Mesopotamian religion, Milgrom contrasts Leviticus’ Priestly

theology with the basic tenets of pagan religion:

Israel’s neighbors believed that impurity polluted the sanctuary.

For them the source of the impurity was demonic. Therefore, their priests devised

rituals and incantations to immunize their temples against demonic penetration.

Israel, however, in the wake of its monotheistic revolution, abolished the

world of demonic divinities. Only a single being capable of demonic acts

remained – the human being. […] Endowed with free will, human power is greater

than any attributed to humans by pagan society. Not only can one defy God but,

in Priestly imagery, one can drive God out of his sanctuary. In this respect,

humans have replaced demons.

Milgrom

unpacks the ritual of the Purification offering (קורבן חטאת,

described in Vayikra 4)

in which “purging blood” is sprinkled, not on the sinner, but rather on the

sanctuary altar. Milgrom contends that:

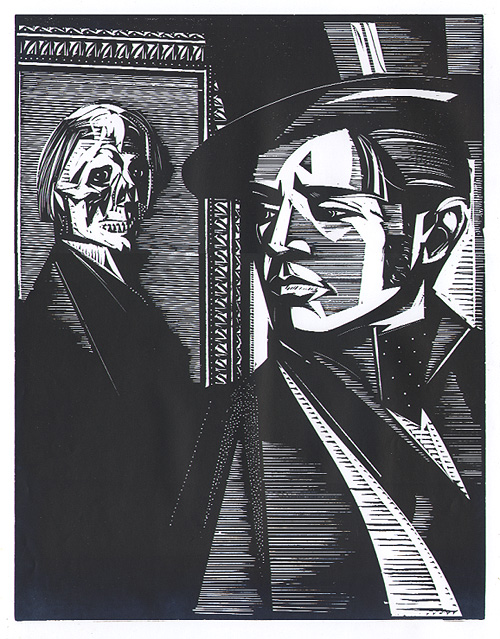

The rationale of the purification [חטאת]

offering [is that] the violation of a commandment generates impurity and, if

severe enough, pollutes the sanctuary from afar. This imagery portrays the Priestly

Picture of Dorian Gray. It declares that while sin may not scar the face of

the sinner, it does scar the face of the sanctuary. In the Priestly scheme,

the sanctuary is polluted (read: society is corrupted) by brazen sins (read:

the rapacity of the leaders) and also by inadvertent sins (read: the

acquiescence of the “silent majority”), with the result that God is driven out

of his sanctuary (read: the nation is destroyed). [Leviticus:

A Continental Commentary, pg. 31-32]

Milgrom

and Leviticus offer us powerful imagery, laden with value-assumptions, with

which to reframe the question of collective responsibility. A “priestly reading”

of this week’s news would suggest that SSgt Bales’ actions polluted the

American sanctuary, thus implying our collective responsibility towards his

act. An obligation ensues for myself and my fellow American to contribute

towards purging the altar.

In

discussing this question, a Bronfman alumna reminded me this week that we must

be careful in discuss our blame and shame of Bales’ actions. In questioning our

share of the responsibility for his actions, we must neither clearing SSgt Bales

of his own responsibility, nor fall to stereotypes of “unhinged” servicemen. The

act of purging for Bales’ deeds might include increasing support for the

families of US soldiers and support for Veterans (through lobbying and

philanthropy), as well as celebrating the daily courageous acts of soldiers,

not just their rare shameful ones.

The confluence

of the murders in France and Afghanistan served as a reminder that as opposed

to the Israelites in the desert, camped around the sanctuary, we live in a

world of complex interlocking and competing identities. Each identity asserts a

different communal “we”. We don’t have just one sanctuary towards which we are

bound, and which collects our polluting and purging acts. We have many:

personally I have a Jewish sanctuary, an Israeli one, an American one, a human one,

a male one, and on and on. To some I feel strongly connected, donating my

half-shekel loyalty tax annually and going on pilgrimages that strengthen my

connection to it. Others I struggle with, only remembering that I am connected

to them when acts of extreme shame or pride occur.

“Words

fall from our lips like the dead leaves of autumn, but rituals endure with

repetition.” Today we have no sanctuary rituals. All we have are the images and

metaphors that our texts have bequeathed us, and our repetitive reading of them.

In those texts, we can find powerful vessels through with to test our ethical

behavior, and the way in which we identify with others. The image of the sanctuary

accumulating our collective misdeeds reminds me that life is not just about

surviving the “news cycle”, but about creating a holy community.

It is

traditional to end Divrei Torah with a touch of redemption. I’m tempted to call

for the messianic rebuilding of the sanctuary, but more relevant would be the

traditional verse said at the end of the week of shiva mourning:

“Death

shall be destroyed forever; and the Lord God will wipe away the tears from all

faces…” (Isaiah 25:8)

בִּלַּע הַמָּוֶת לָנֶצַח, וּמָחָה אֲדֹנָי ה' דִּמְעָה מֵעַל

כָּל-פָּנִים

Dedicated to the memory of Jonathan Sandler;

Aryeh son of Jonathan Sandler, Gavriel son of Jonathan Sandler; Miriam Montsengo; as well as (as

reported online):

Mohamed Dawood son of Abdullah; Khudaydad son of Mohamed Juma; Nazar Mohamed;

Payendo; Robeena; Shatarina daughter of Sultan Mohamed; Zahra daughter of Abdul

Hamid; Nazia daughter of Dost Mohamed; Masooma daughter of Mohamed Wazir;

Farida daughter of Mohamed Wazir; Palwasha daughter of Mohamed Wazir; Nabia

daughter of Mohamed Wazir; Esmatullah daughter of Mohamed Wazir; Faizullah son

of Mohamed Wazir; Essa Mohamed son of Mohamed Hussain; Akhtar Mohamed son of

Murrad Ali.