Rabbi Mishael Zion | Bronfman Fellowships | Text and the City | Shemot 2013

I am not a big believer in New Year’s Resolutions, whether they come in Tishrei or in January. They feel like a tokenistic, gratuitous act, to be flicked off like a dry scab a few weeks into the New Year. Yet sometimes it is the smallest shift of focus which can open the door to enormous change. Inspired by the first Parasha of the new year, Shemot, I aspire this year to give a new twist to the most mundane of acts: seeing.

A strange midrash describes our ancestor Primordial Adam as having the ability to see “from one end of the world to the

other”. This might be classic rabbinic hyperbole, but compared with, say –

1813 - we in our generation have again reached the ability to “see from one end

of the world to the other” - from the comfort of our mobile device. This

information revolution has raised awareness to many ills, and spawned

revolutions where before ignorance and oppression reigned. At the same time, it

has created a “compassion fatigue” where headlines come and go and we become increasingly

cynical and unsympathetic. Faced with the ability to hear endless points of

view on any issue we are increasingly putting on the horse blinders of

parochial media outlets, creating homogeneous virtual villages of our own ideasas our fatigued eyes close to all things that don’t already fit our view.

With the ability to see

everything, a new “ethic of seeing” is required, for what and how we see

is the key to all moral behavior.

The opening of the book of Exodus makes a similar point. In the portion which

will be read by Jewish communities the world over on the first Shabbat of 2013,

Parashat Shemot describes how the distorted sight of Pharoah turns the Children of

Israel in Egypt from upright citizens to dangerous others; then to invisible slaves; to the objects of genocide; and finally to candidates for annihilation.

| “The Mother of Moses,” Simeon Solomon 1860 |

Or so it would have happened if not for the moral courage of

a handful of women, who are described again and again as simply – seeing.

The term “to see” appears 22 times in the first three chapters of Exodus, essentially

every third verse. When Pharaoh orders two midwives to kill any Israelite baby

boy they see, they instead “see God” and refuse to kill. In a

description evocative of God’s seeing in Genesis Chapter 1, a young mother “sees

that her child is good” and places him in an ark. Consequently, Pharaoh’s daughter “saw

the little ark among the reeds… opened it and saw him, the child!” It is this seeing which is immortalized in Moses’ name: “She

named him Moshe, He-Who-Pulls-Out; saying: “For out of the water I-pulled-him

(meshitihu).” Ethical seeing is the pre-requisite to any act of moral

salvation.

True to both his biological and

adopted mothers, Moses is a person dedicated to ethical seeing. Upon entering

adulthood, Moses has the entire world open to him. Yet his first act is described

as follows: “He went out to his brothers – to see in their

burdens.” Rashi points out that this is not a simple act of sightseeing,

rather:

“He directed his eyes and his heart to share

their distress.”

|

וירא

בסבלתם: נתן עיניו ולבו להיות מיצר עליהם:

|

Rashi astutely points out that

the heart follows the eyes. To truly “see” is an act of the heart, not just the

eyes; it is an act of deep compassion. What are the ethics of sight according

to Exodus Chapter 1-3? Inspired by young Moses, one must “see in their

burdens” – to see with heart as well as with eyes, in a directed manner, fighting off compasion fatigue.

Moreover, it is about “going out” – going beyond our regular circles of

information to gain new (in)sight.

How does this translate into action for 2013? For our information addled generation, we must be purposeful about where we direct our sight. Since the primary way we “see” today is by consuming written and visual media, we must curate out information guided by moral vision. We must “go out” of our usual information silos, reading opinions and reports we disagree with, consuming media in a purposeful way and from a myriad of perspectives, overcoming our compassion fatigue. In the last confrontation between Israel and the Hamas, I attempted to consume media with purpose: reading and watching an increased amount of TV from “my brothers” in Israel, but also “going out” and reading about the plight of Palestinians and seeking out the perspective of Al Jazeera. I read the analysts who preached to my comfort zone (Haaretz?), as well as the pundits whom I vehemently disagree with (Arutz Sheva? When I disagree with them they are always pundits…). “Going out” does not mean not taking sides – I know who “my brothers” are – yet I feel there is an ethical imperative to constantly widen my lens of sight, in all directions.

Beyond virtual consumption of

media, “going out and seeing” is to be done in person and in our local

communities. I salute those who simply drove out to Newtown, the Rockaways or

Beer Sheva, to see first-hand and “share their distress”, not to mention

lending a hand. Yet seeing ethically also begins right in our backyard, seeking

out those who are invisible to us. There are few experiences more degrading than feeling that one is not seen. Like Pharaoh’s daughter, we must seek those hidden by the reeds

whom we have trained our eyes not to see, and refresh our seeing of them. We

must “go out… and see”.

|

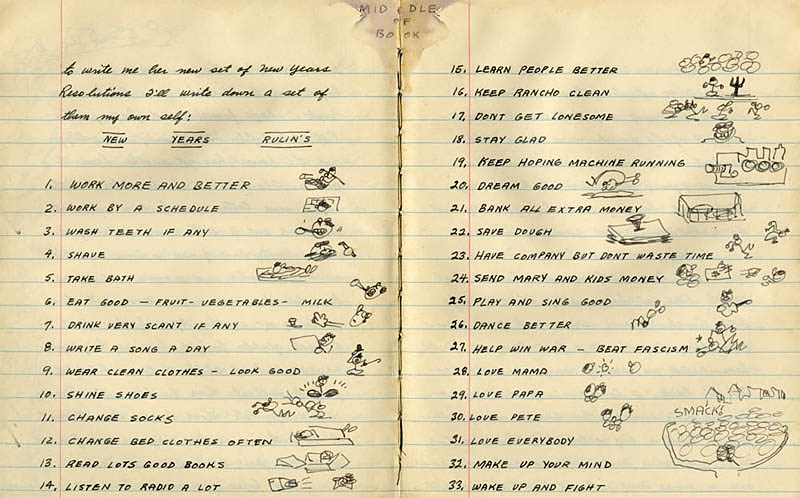

| Woody Guthrie's New Year's resolution, 1943 |

We might not be able to right

all the wrongs of the world in 2013, but seeing them is the first and crucial

step towards a better year for all. I hope to still be seeing in this new light

in February, continuing to explore and refine what "ethical seeing" means in the 21st century. If you see me around, please nudge me to keep it up.

Happy 2013,

Mishael

Gods, while tourists twirl around him on the ice-skating rink. Above the statue a quote from Aeschylus reads: 'Prometheus, teacher in every art, brought the fire that hath proved to mortals a means to mighty ends.'

Gods, while tourists twirl around him on the ice-skating rink. Above the statue a quote from Aeschylus reads: 'Prometheus, teacher in every art, brought the fire that hath proved to mortals a means to mighty ends.' tyrannical Gods (or traditional authority, the Catholic church, the Monarchy). For young Modernists seeking to remove the yoke of a cold and cruel religion that seemed determined to keep them shackled to the past rather than move forward, Prometheus was the hero, having redeemed humanity from their dependence on God by stealing fire from Zeus. To the Romantic mind, Prometheus was the creator of a new race of people, unafraid to rebel against the Gods, as Goethe describes in his poem, Prometheus, written the same year as the French Revolution:

tyrannical Gods (or traditional authority, the Catholic church, the Monarchy). For young Modernists seeking to remove the yoke of a cold and cruel religion that seemed determined to keep them shackled to the past rather than move forward, Prometheus was the hero, having redeemed humanity from their dependence on God by stealing fire from Zeus. To the Romantic mind, Prometheus was the creator of a new race of people, unafraid to rebel against the Gods, as Goethe describes in his poem, Prometheus, written the same year as the French Revolution: in our hardest moment; God who commanded us to light candles. As opposed to the Gods of Idolatry, Judaism purports a covenant, an on-going, mutual relationship between the creator and the creatures. We are not in competition, but in cooperation, and God is invested in our technological advancements – as long as they benefit the project of creation. Hanukkah – and the other seasonal festivals of light – come at the darkest time of the year, when we feel most acutely the cold shoulder of this world. It is precisely at this time that we embrace fire – not as a sign of human rebellion but as a sign of the partnership we have with creation (and for some of us, with the Creator). This partnership can be defined thus: When the world is dark, we must shine forth.

in our hardest moment; God who commanded us to light candles. As opposed to the Gods of Idolatry, Judaism purports a covenant, an on-going, mutual relationship between the creator and the creatures. We are not in competition, but in cooperation, and God is invested in our technological advancements – as long as they benefit the project of creation. Hanukkah – and the other seasonal festivals of light – come at the darkest time of the year, when we feel most acutely the cold shoulder of this world. It is precisely at this time that we embrace fire – not as a sign of human rebellion but as a sign of the partnership we have with creation (and for some of us, with the Creator). This partnership can be defined thus: When the world is dark, we must shine forth.